Perhaps culture’s most important mission is to be a helping hand in times of misfortune.

During the last year, we Ukrainian artists have often asked ourselves: what can culture do in bad times?

Culture cannot stop war, cannot dissuade an enemy who has come to kill us.

Culture cannot rebuild our houses, demine our fields. As for the dead, it can only mourn and commemorate them. It cannot even collect their bodies, which may lie untouched under shelling for weeks.

So, what can it do?

When the full-scale Russian invasion began, I immediately started volunteering at the train station in Lviv where tens of thousands of forcibly displaced people from the frontline regions were arriving. My job was to provide them with hot drinks, food, and information, and to listen to those who wanted to talk. Later I accompanied them to refugee shelters. Every day I went there with a backpack full of my personal documents and everything I needed to survive, because I didn’t know if I would be able to return home.

The greatest wonder in those days was that in the evenings when I was coming home, my home still existed, with its walls, with its books, with the cat needing petting and begging for food.

On the third or fourth evening, I began to read. It was a strange and counter-intuitive action because reading seemed dangerous to me. I felt like I would lose control of reality if I entered another person’s world even for a moment. Nevertheless, I read. I read the autobiographical stories of Ida Fink, a Jewish woman who was born in Ukraine and escaped the Holocaust with her sister. She went through the worst: looters, forced labor, the Gestapo, concentration camps. You may wonder: haven’t I had enough horrors in reality?

But this book seemed to lead me by the hand. The heroine, who goes through the horrible misfortunes of war, finally leaves one simple but important message: if I could do it, so can you. It is unlikely that something more terrible will happen to you.

Perhaps this is the most important mission of culture, often not visible from the perspective of so-called “peaceful” times: to be a helping hand in misfortune. Stretched across time and miles, this hand finds the one who needs it. The outstretched hand offers not an admonition, not an instruction, not a demand, not a call, and not a rebuke, but simply a touch that expresses what is said, without speaking, in Ida Fink’s text: “I could do it, therefore, you can too.” These connected hands create a chain that stretches through time, and the best thing you can do if you want to say thank you is to try not to break the chain.

“Ukrainian culture now, as perhaps never before, works as one organism. From memes and graffiti to classical music, everything channels the same energy.”

An outstretched hand will not hang by itself in the air, because—let’s not deceive ourselves—there have never been and, most likely, there will not be any “good” times. “Peace” is a moment of calm while someone reloads their weapon. “Peace” is the time when the war recedes from our windows, when we are busy looking at other things, so that one day it will definitely remember us.

After recovering from the first shock of invasion, we Ukrainian artists started to create. We watched, listened, memorized, and then wrote, drew, or performed. We continue today, though it is still not easy, because neither our language nor our imagination was ready for such a reality. But no one will do it for us, no one will do it later.

Ukrainian culture now, as perhaps never before, works as one organism. From memes and graffiti to classical music, everything channels the same energy. This is not the “synthesis” we used to talk about in peacetime, but something else: it is a kind of mobilization needed for a joint rush toward the same goal. This is the circulation of values.

Everything we create now will not just be a testimony of bad times. I hope, like Ida Fink’s stories, it will also become a helping hand for someone. For someone who will need it one day. ◆

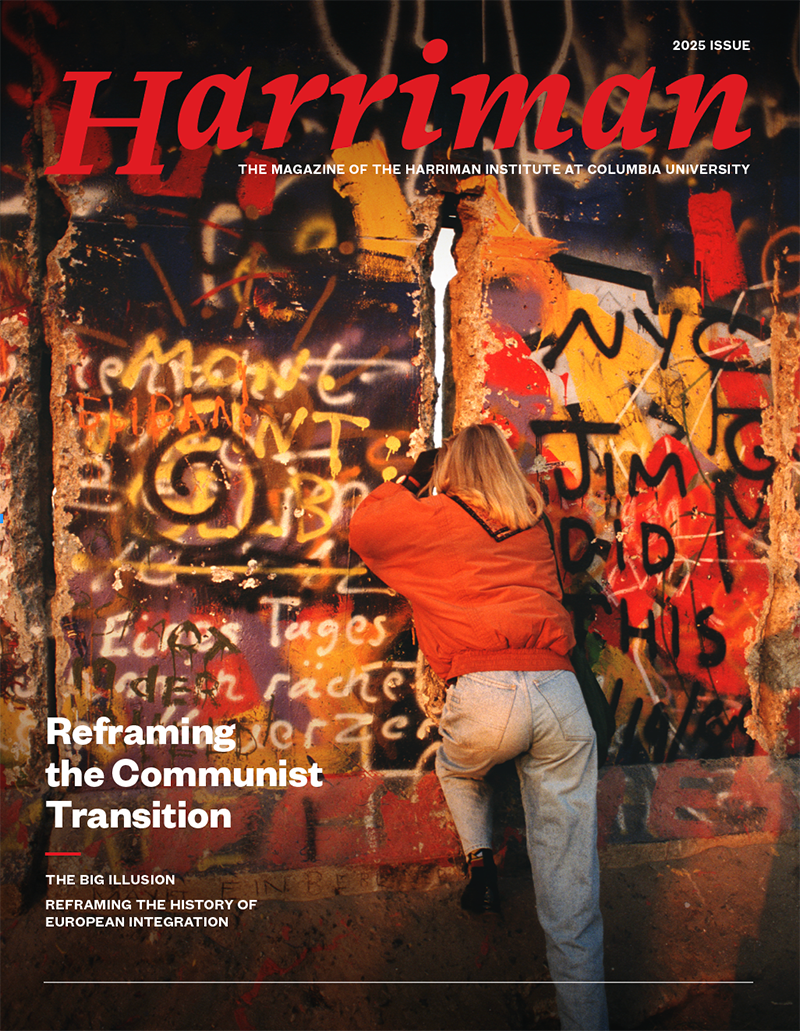

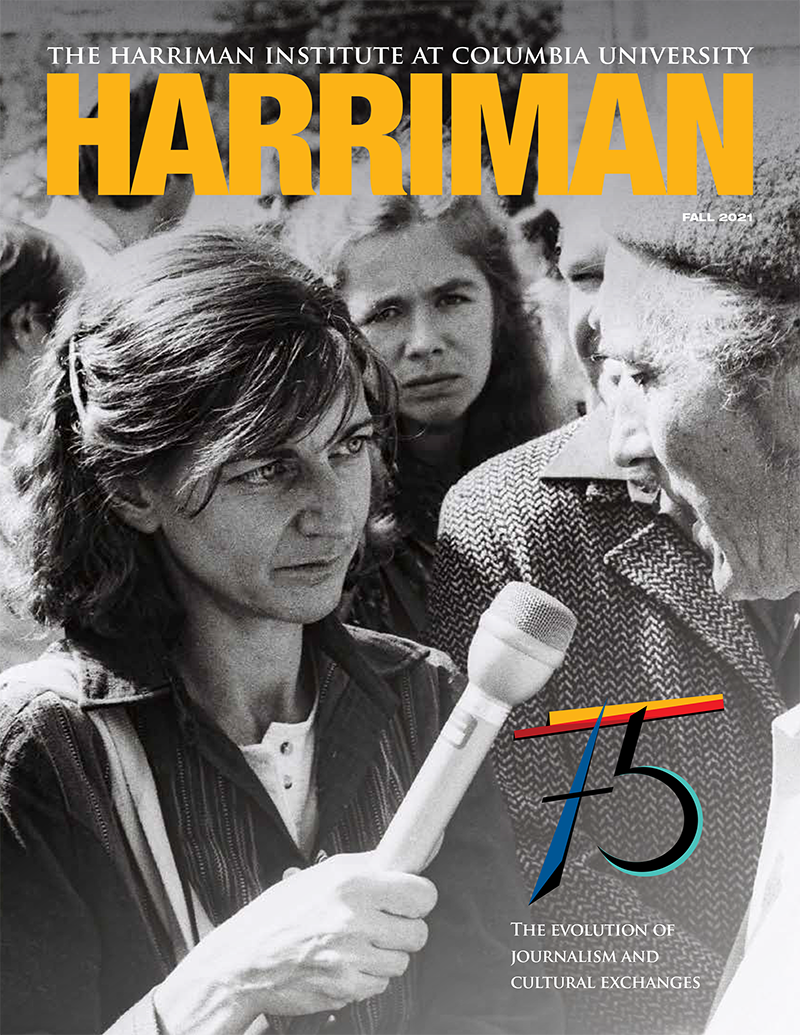

Featured photo (at the top): Left to right: Nikita Yermak, Ihor Barynin, Lavinia Pavlish, Valeriya Sholokhova performing Ukrainian music for a string quartet curated by Anna Stavychenko for Art in Time of War. Photograph by Eileen Barroso.

The works linked below are from Harriman’s four 2023 Ukrainian residents in Paris, who participated in Art in Time of War and then continued their artistic residencies at Reid Hall, Columbia Global Centers in Paris.

The Second Beginning

By Nikita Grigorov, who is a Ukrainian writer, journalist, and editor selected as the Harriman Institute’s 2022 Paul Klebnikov Fellow. Translated from the Russian by Masha Udensiva-Brenner. Read now >>

Kateryna

By Natalka Bilotserkivets, an award-winning Ukrainian poet. Translated from the Ukrainian by Ali Kinsella (MARS-REERS ’14) and Ukrainian-American poet and translator Dzvinia Orlowksy. Read now >>

To See Beauty Again

By Anna Stavychenko, Ukrainian musicologist, former executive director of the Kyiv Symphony Orchestra, and mission head of the Philharmonie de Paris project that helps Ukrainian musicians exiled in France. Translated by Masha Udensiva-Brenner. Read now >>

The Smell of Mariupol

By Zoya Laktionova, Ukrainian documentary filmmaker. Read now >>