In the wake of the American agency’s dismantling, experts worry about how the absence of U.S. assistance will affect Moldova’s future.

When the Trump administration targeted U.S. foreign aid programs for oblivion in early 2025, aid defenders predicted alarming consequences. Among them: Millions of people, in places ranging from Vietnam, to Uganda, to Haiti, would be at risk if America ended programs to vaccinate children and fight HIV/AIDS, malaria, tuberculosis, and other infectious diseases.

But in Eastern Europe and Eurasia, the predictions were different: Most likely at risk were the democratic institutions that Western aid has sought to foster in the region since the collapse of the Soviet Union.

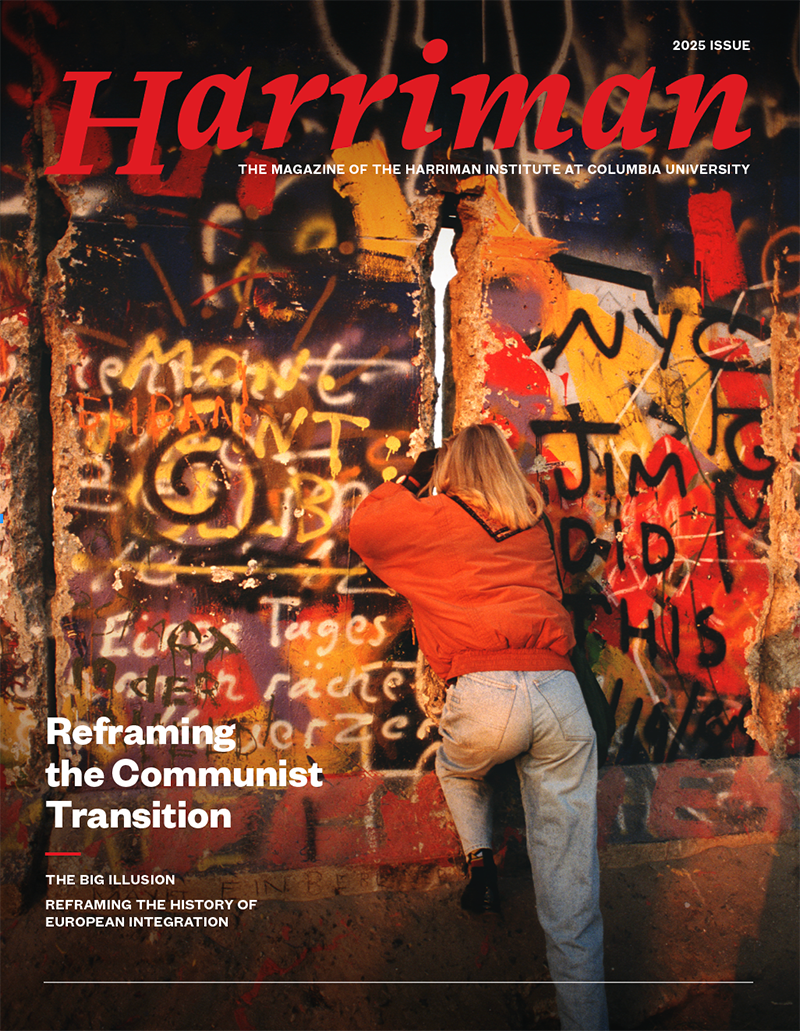

Now that the administration has made its sweeping cuts, Moldova, the small, landlocked former Soviet republic sandwiched between Romania and Ukraine, is one barometer to watch for the impact. There, a pro-European Union government won a vital election victory in September 2025 despite Russia’s vigorous efforts to spread political disinformation and interfere in the balloting. While pro-democracy forces could celebrate that victory, no one expects Russia to abandon efforts to bring Moldova into its sphere of influence, and the U.S. foreign aid cuts create an opening for Russia’s operations to have more impact in the future.

Since the end of the Cold War, U.S. assistance to Moldova (as well as the region at large) has focused to a large degree on democracy promotion and the building of institutions needed to sustain it: free and fair election processes, independent media, judicial reform, anti-corruption enforcement, and protections for human rights. Among the leading American agencies supporting these programs were the now largely defunct U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), the State Department, the U.S. Agency for Global Media (the parent agency for the embattled Voice of America and Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty), and the National Endowment for Democracy (NED).

A balance sheet for the decades of work and billions of dollars of aid sent to Eastern Europe and Eurasia would show mixed results, to say the least, in spreading democracy. At one end, U.S. and other Western support has helped the small Baltic states of Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia become solid members of NATO and the European Union. At the other end is giant Russia, where optimistic pro-democracy programs of the 1990s have all crumbled under the increasingly autocratic rule of Vladimir Putin.

Somewhere in between lies Moldova, where for years after independence, voters kept swinging their allegiance between pro-EU leaders and corrupt oligarchs, the latter often aligned with Russia. Though voters have twice elected pro-EU President Maia Sandu and had narrowly approved a referendum in 2024 endorsing Moldova’s bid to join the EU, the parliamentary elections of September 2025 were predicted to be extremely close—and vulnerable to Russian interference.

“A Defining Vote in a Fragile Democracy” is how the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change described the ballot, where “Moscow’s intensifying hybrid interference” could “determine whether the country stays on course to join the European Union or veers down a different path.”

European concerns about the elections may have been fed by President Donald Trump’s early 2025 decision to kill most of America’s soft power aid programs aimed at countering Russian influence. In his 2025 State of the Union address, Trump cited “$32 million for a left-wing propaganda operation in Moldova” as an example of “appalling waste” in U.S. foreign aid. Although the president didn’t specify what he was referring to, it’s likely the so-called “propaganda operation” was a USAID program to help Moldova conduct free and fair elections. Over the years, U.S. funding has trained monitors and supported the institutions that oversee Moldova’s elections; Trump’s abrupt aid cuts eliminated that support just months before the September 2025 ballot, sending election overseers scrambling for other resources to monitor the vote. The need for election vigilance was apparent as Russia bombarded the country with disinformation, such as unsubstantiated claims that President Sandu was schizophrenic. And less than a week before the polls opened, Moldovan officials arrested 74 people, charging they were part of a Russian plot to incite “mass riots” and disrupt the balloting.

In spite of the risks to democracy in Moldova and many other countries, Trump made his move to cut foreign aid shortly after naming Elon Musk head of an unofficial Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE). Musk quickly took aim at USAID, calling it a “criminal organization.” Trump chimed in that it was “run by a bunch of radical lunatics.”

Promo-LEX short-term election observers on the day of Parliamentary elections held in the town of Cahul, Moldova in September 2025. Photo courtesy of Promo-LEX

But many Moldovans who believe the country belongs in the European Union (as many as 63 percent in one 2025 survey) value the aid received from the United States.

“It’s no exaggeration to say that we have democracy in Moldova, in part thanks to American financial support,” Valeriu Pasa, the chairman of the Chisinau-based thank-tank WatchDog, said in late January 2025. The United States, Pasa said, benefits “from us being more democratic and developed, ensuring we don’t turn into a Russian or Chinese colony.”

Such arguments did nothing to stop the dismantling of USAID and other aid programs—a process carried out without “considering the risks and damages to countries like Moldova,” said Igor Botan, executive director of the Association for Participatory Democracy in Chisinau, and “even though Moldova had a special relationship with the U.S. benefitting from economic and other types of support.”

The pro-EU win in the 2025 elections has created a temporary sense of relief among European leaders and pro-EU Moldovans. Analysts credit the victory in part to the coverage of Moldovan and foreign investigative media—which worked to expose Russia’s interference efforts and domestic corruption—and also to European leaders, who, after the Trump administration rolled back U.S. foreign aid, stepped in to fill much of the financial gap for the election protection efforts in Moldova. But even with the pro-EU Maia Sandu in power, it remains to be seen how Moldova’s democratic institutions will be affected by the loss of U.S. aid. And it’s a given that Russia will keep trying to pull Moldova into its orbit.

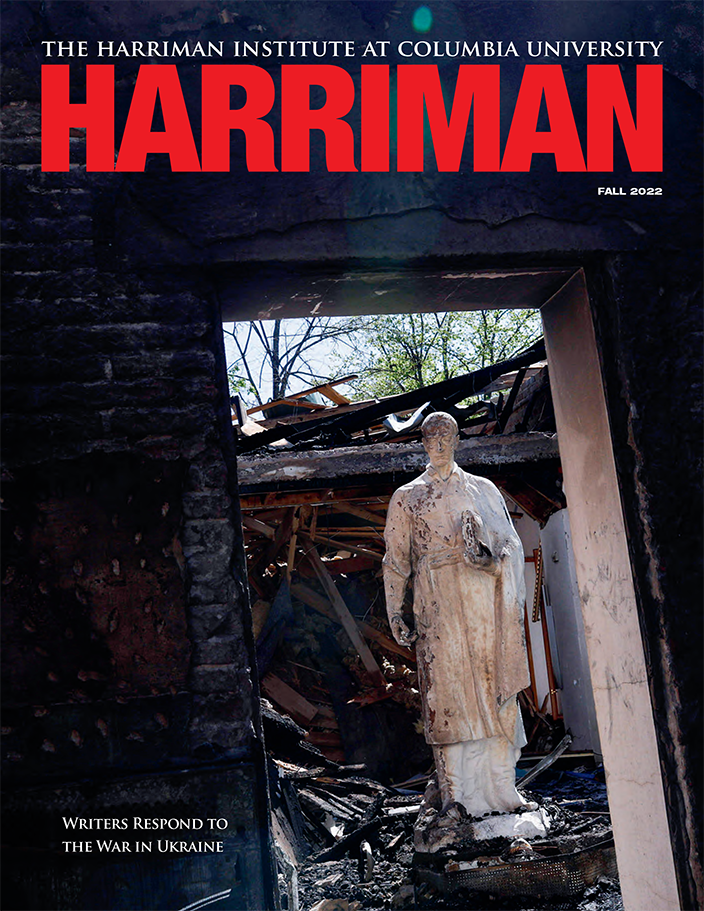

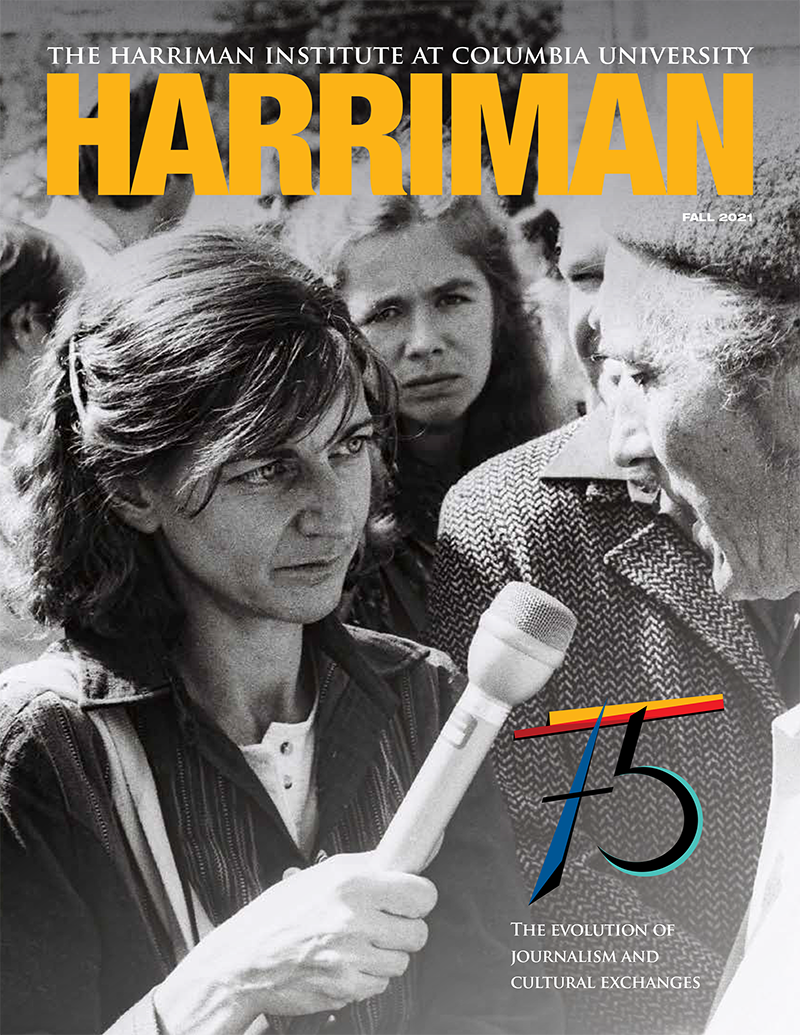

Voice of America, RFE/RL and the various language services of America’s international broadcasting were long viewed as among America’s most potent soft power tools in its battle against Soviet Communism. Then, at the end of the Cold War, some argued that these programs had served their purpose and could be eliminated. But Eastern European leaders such as Lech Wałęsa and Vaclav Havel urged America to keep them in place. Communism may have fallen, but new institutions had to be built, and there were no guarantees they would follow examples of Western democracy.

Independence also did not resolve thorny regional conflicts left over from the Soviet era, like the status of Transnistria, a sliver of territory between Moldova and Ukraine where a Russian military base and a Soviet-era ammunition depot remained after independence. Though Transnistria is multiethnic, Russian language dominates, and the region has established its own currency, education system, and other structures inspired by Russia (though neither Russia nor any other country has ever recognized it as a state officially independent from Moldova).

As the Transnistrian conflict continued to simmer, Moldovans in the 1990s had to come to grips with the reality of independence. With a population of just 2.9 million at the time (currently closer to 2.4 million, due to the “brain drain” of Moldovans leaving for other more prosperous European countries) and an economy that put it near the bottom of Europe in terms of wealth, independence euphoria was fleeting. Many were nostalgic for the Soviet, pre-planned past of their youth, when jobs and housing—however inadequate they might have been—were guaranteed by the state. There was little patience for promised reforms that were slow to deliver on privatizing state property, land reform, and political change. Demands for free school lunches, heat assistance in winter, and health programs to combat diseases such a tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS competed for money and attention.

In the early years of independence, the United States stepped in with aid meant to address some of these issues. A USAID timeline of its work in Moldova lists 130 projects it funded over 30 years. (According to Moldovan Prime Minister Dorin Recean, USAID had allocated more than $1 billion in Moldova before most aid ended in 2025.)

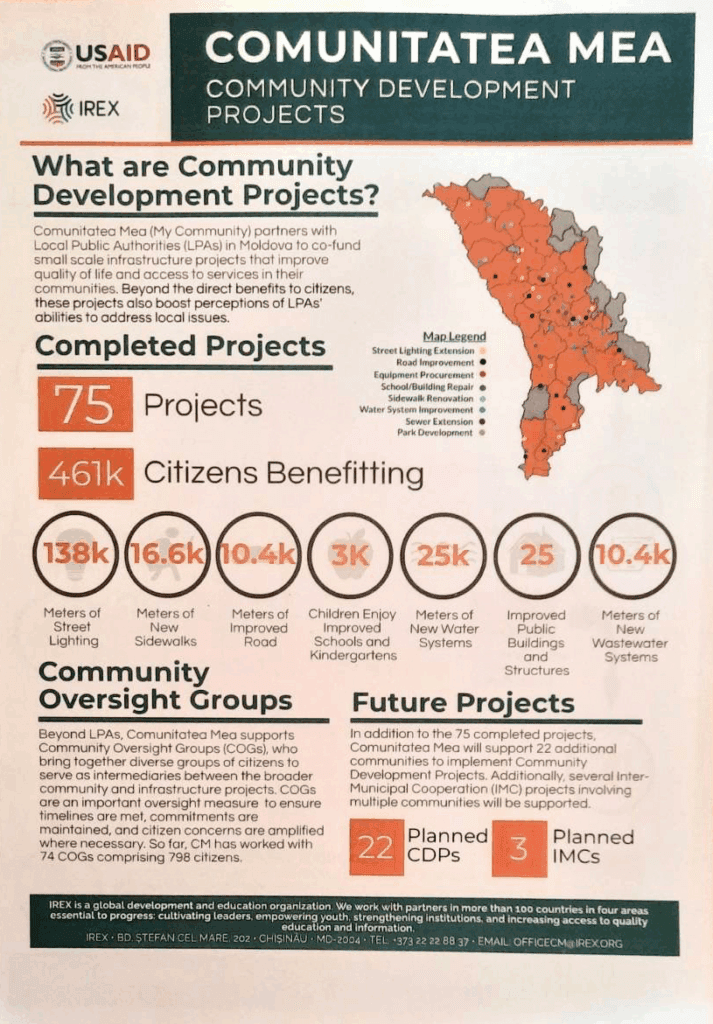

One-pager of the USAID funded project Comunitatea Mea (My Community) implemented by IREX in Moldova.

The first USAID projects in Moldova began just two years after independence in 1993, and their focus reflected some of the most pressing needs of that time: helping the country privatize property and enterprises; restructuring the collective farms of the Soviet era; and teaching entrepreneurship to farmers. Other programs promised assistance in reforming accounting and commercial law or offered social support in the form of food aid, health insurance, or reproductive health programs for women.

By the early 2000s, the USAID timeline shows some significant shifts, with more programs focused on economic development and better governance—reform of telecommunications, strengthening digital security of government records, and developing resources that would make Moldova less dependent on Russian energy. But Moldovans still struggled economically, and many who sought to leave to seek better opportunities fell prey to human traffickers; USAID was among the global agencies whose efforts eventually eased the trafficking crisis.

Along the way, USAID funded a variety of programs aimed at promoting civic engagement in politics, ensuring free and fair elections, and reforming the judicial system by vetting judges (some of whom were pressured to leave the bench after investigations exposed corrupt behavior). USAID also started prioritizing the development of some of Moldova’s most important economic sectors—wine, information technology, and fashion. The wine industry is a great example of a successful U.S. soft power effort. As recently as 30 years ago, Moldova’s wine exports were mostly to Russia. After USAID programs promoted the production of better-quality wines and effective ways to market them, the bulk of Moldova’s wine exports now go to western countries. Shifts like these were designed to reduce Russia’s economic and political influence in Moldova, and they were ushered along with programs sponsored by USAID.

In the wake of the 2025 parliamentary election, Moldovan officials expressed gratitude to the European Union and individual European countries that had denounced Russian interference and offered assistance to help ensure free and fair balloting. There was also praise for Moldovan investigative journalists, a small community fostered with financial support from the United States and other foreign governments that has played a key role in building a democratic foundation in Moldova.

One of the most ambitious journalistic investigations came in 2024, when President Maia Sandu ran for reelection to a second term, and voters cast ballots in a referendum on whether the country should continue efforts to join the European Union. As usual in recent Moldovan elections, competition was fierce between Sandu’s pro-EU Party of Action and Solidarity and other parties whose platforms shun the EU in favor of strengthening Moldova’s ties to Russia.

Ultimately, Sandu and the campaign for EU membership won narrowly in the balloting. But in the wake of those victories, police launched an investigation into some bombshell allegations: that Russian-backed forces paid tens of thousands of Moldovans in an unsuccessful campaign to defeat Sandu. Eventually some 25,000 voters were fined for accepting bribes for their votes—though the accused mastermind of the scheme, oligarch Ilan Shor, avoided punishment because he lives in exile in Russia. (Shor fled Moldova to avoid a prison sentence for his role in a scheme that stole a stunning $1 billion from Moldovan banks in 2014.)

The vote-buying scandal was revealed by undercover investigative journalists for Ziarul de Garda (ZdG) one of several independent media outlets supported over the years by grants from the American embassy in Chisinau, USAID, the National Endowment for Democracy, and European funders. To the extent that watchdog and investigative journalism exists in Moldova, exposing corruption and monitoring the performance of elected officials, it is largely thanks to ZdG, Agora, NewsMaker, RISE Moldova, CU SENS, and others in the limited sphere of independent media. But their resources, and the size of their audiences, are overshadowed by the more than 50 percent of Moldovan media controlled by wealthy politicians or businessmen.

The independents are long on enthusiasm but always short on funding. To address that issue, in 2017 USAID initiated a new program, MEDIA-M, aimed at helping them learn new business and management skills. Internews, a U.S.-based NGO created to work globally on media development, won the USAID contract for MEDIA-M. The journalists, legal experts, and others—some local, some brought in from Romania, Ukraine, and other European countries— focused on how to establish human resources policies, develop strategic planning, and build systems for digital and physical security. Oligarchs held political sway at that time, and legal training for the independent journalists was also crucial, as they faced lawsuits from officials and others for exposing corruption.

A frequent target was the indefatigable journalist Alina Radu, who had previously reported for state and private media outlets, leaving those jobs when politicians intervened to dictate how the news should be covered. In 2004, with a small grant from the Romanian government and not much else in the way of resources, she and a friend founded Ziarul de Garda as an investigative newspaper. Somehow, with support from various western embassies and other donors in Europe, it survived to 2017, when MEDIA-M started.

ZdG began covering more breaking news and using video as part of its storytelling, which helped build its audience—and reduce, to some degree, reliance on foreign funding. Then, in 2024, came its bombshell story, based on undercover reporting by a ZdG staffer who worked in the Russia-backed network that paid people to attend anti-Sandu rallies and to vote against the president and her drive for EU membership. The news was so sensational that it couldn’t be ignored by other media; videos made by the ZdG site were played on broadcast media throughout Moldova, and the site’s coverage of the vote-buying scandal won awards in Europe for investigative journalism.

Radu says ZdG is able to carry out such investigations in part because of what she learned “from American organizations: management skills, proper planning, and transparency.” But now, she said, “the same American organizations canceled the funding with no warning.”

The abrupt manner in which funding ended, and the hostile rhetoric from Elon Musk and President Trump, had a fallout effect for Radu. While her site won praise in 2024, including from Moldovan police and the speaker of parliament, pro-Russian parliamentarians launched a vocal attack campaign in 2025, denouncing ZdG as a criminal organization—because it was funded by USAID, another “criminal” organization (as characterized by Musk).

In the months following the Trump soft power cuts, ZdG and other independents remained in business, but the sea change in U.S. policy and funding sent a chilling signal. “It felt like the Russian and the U.S. governments allied over attacking the independent press,” said Radu.

The cuts in USAID and other funding had wide-ranging immediate effects in Moldova. Several infrastructure projects lost funding, including $300 million in USAID money to reduce Moldova’s energy dependence on Russia (though the United States later said it would restore $130 million of the USAID program to build a high voltage power line to Romania that would connect Moldova to the European electricity grid).

Children walk by a banner for a USAID-supported project extending the fire hydrant network in the village of Sireti, Moldova, in January 2025. AP Photo/Aurel Obreja

Some cuts, made just months before the crucial parliamentary elections, had the potential to affect the campaign. Promo-LEX, a nonpartisan NGO that has monitored Moldovan elections for more than 20 years, lost the U.S. funding that was its main revenue source. The monitors were still functioning for the September ballot, though, thanks to emergency funding provided by European governments (and some from the United Nations). But how it will be funded going forward is unknown, said Promo-LEX founder Ion Manole.

“We’re grateful to the U.S. for its past generous support. It’s U.S. money, so it’s their decision to continue giving it or not,” said Manole. “Some advance notice would have been better, though.”

The Moldovan parliamentary elections results have proven that investments supporting democratic processes, including in media literacy, countering disinformation campaigns, and supporting independent content providers, have a real impact. The EU and individual European countries understood that when Promo-LEX and others sought their support to make up for the U.S. cuts. The 2025 parliamentary elections gave special urgency to those requests. But the impact of U.S. cuts continues well beyond last year’s election emergency, and Moldova’s long-term political future remains very unclear.◆

Corina Cepoi has over 25 years of experience in media development and strategic leadership, including managing the Internews MEDIA-M project in Moldova. She founded the School of Journalism in Moldova and served as director of the country’s Independent Journalism Centre for 12 years.

Featured Image: Then-U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken joined Moldovan President Maia Sandu for a joint press conference in Chisinau in May 2024. Blinken visited Moldova to show strong U.S. support for the country’s Western aspirations. Photo by Vadim Shirda/POOL/AFP