After Russia invaded and occupied Crimea and parts of Eastern Ukraine in 2014, sending U.S.-Russia relations plummeting to a low point not seen since the Cold War era, policymakers in U.S. government wondered whether a decline in U.S. academic expertise on Russia had contributed to the crisis. But there was no existing data on the health of Russian studies in the United States. That prompted Carnegie Corporation of New York to commission a study on the state of research and graduate training on Russia in U.S.-based academic institutions.

The resulting report by the Association for Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies surveyed 26 U.S. universities and 660 Russia-focused researchers, U.S. government officials, think tanks, and more. Its conclusion: While Russian studies remained strong overall, “Russian studies within the social sciences [in this case meaning anthropology, economics, political science, and sociology] are facing a crisis: an unmistakable decline in interest and numbers, in terms of both graduate students and faculty.”

To address that shortcoming, Carnegie awarded three competitive $1 million grants to U.S. academic institutions working on Russia, including the Harriman Institute. A 2016 press release announcing the grants said they would “encourage universities to build up Russia-relevant training, research, and outreach programs” and increase their engagement with Russian academic communities.

Alexander Cooley, Claire Tow Professor of Political Science at Barnard College and director of the Harriman Institute when the grant was announced, became Harriman’s lead principal investigator on the project. An early initiative by Cooley was the monthly New York Russia Public Policy Seminar with Joshua Tucker, director of New York University’s Jordan Center for the Advanced Study of Russia. The seminars brought together scholars and policymakers to discuss issues of critical importance in U.S.-Russia relations. Topics ranged from Russian influence in the 2024 Georgian elections to wartime emigration and the Russian diaspora, and developments in Russian-occupied territories of Ukraine.

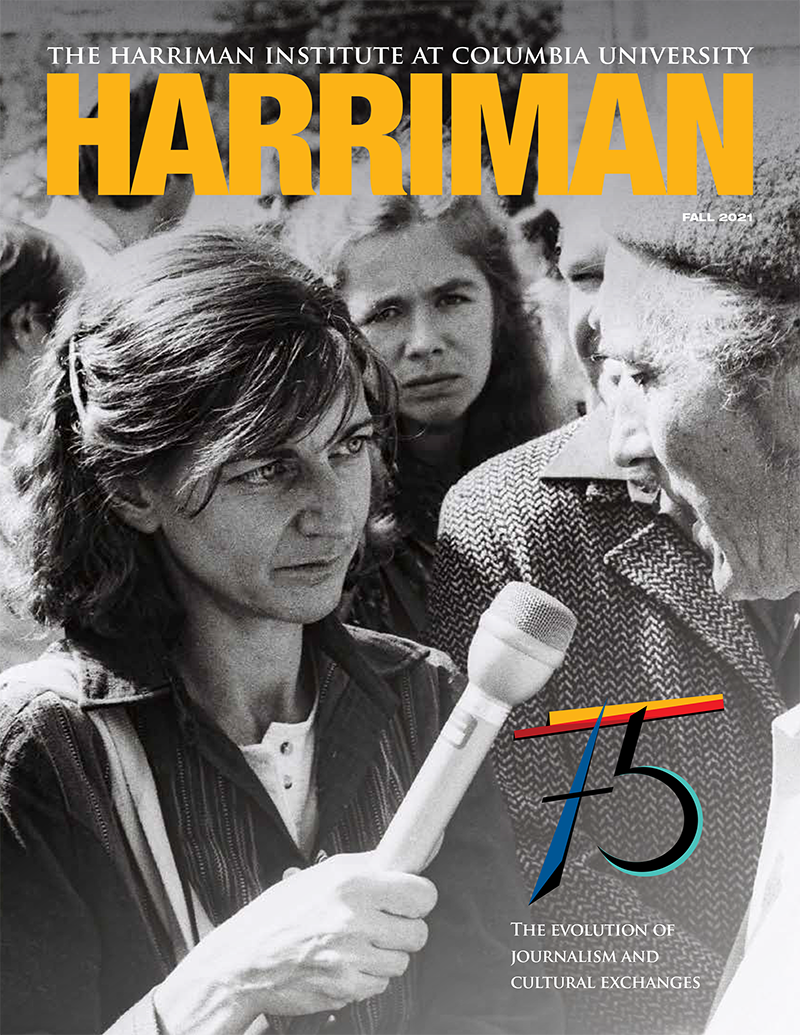

One of the early series highlights was a 2017 public debate between former U.S. Ambassador to Russia Michael McFaul and the late Russia historian and public intellectual Stephen Cohen. “The two differed on the root causes of Russia’s annexation of Crimea,” said Cooley, “but the debate was respectful, fact-based, and encouraged foreign policy experts and commentators to prioritize formulating a strategic policy toward Russia.”

Elise Giuliano, another Carnegie principal investigator and the director of the Harriman Institute’s MARS-REERS Master’s program, ran a separate speaker series called the Program on U.S.-Russia Relations (PURR). PURR was founded earlier, in 2015, by Kimberly Marten, Professor of Political Science at Barnard College, who continued expanding the series for several years. While Cooley’s seminars focused on current events, PURR talks invited scholars and policymakers to reflect on longer-term issues—such as the state of Russian domestic politics and Russia’s relations with China, Turkey, the Koreas, Latin America, and Africa.

“We invited not just American policy specialists but also people with local knowledge” from regions around the world, said Giuliano.

A third program enabled by the Carnegie grant provided grant money to graduate students across the United States for dissertation research on Russia-related topics and for conference travel to Russia. Timothy Frye, who directed the Harriman Institute before Cooley, oversaw the grant program.

“The big picture was to create a cohort across universities of graduate students working on Russia,” Frye said. “Funding for studying the region has been going down, so this was a lifeline for many students, some of whom were at state universities where getting travel funds is really difficult.”

Unfortunately, research trips to Russia, as well as academic exchanges led by Cooley to bring together Russian and U.S. doctoral students from Columbia and the Institute of World Economy and International Relations in Moscow (widely known as IMEMO), were cut short by the COVID pandemic in 2020. Then, after Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, all such travel was brought to an official close.

“We can’t do exchanges anymore, we can’t really engage with Russian academics and scholars, and there are also sanctions that prevent us from paying Russian nationals,” said Cooley.

“Those were really challenging inflection points.”

But Frye said the Institute was able to get creative with the funding, “Often projects evolved and took on an international character,” he said. “Students applied to study topics using archives in the Baltics or Bulgaria, or other places outside of Russia and Ukraine, to study Russia and the former Soviet Union.” And the Harriman Institute continued to invite graduate students from across the nation to Columbia for conferences.

“The grants built a sense of community among graduate students at different universities,” said Frye, with many papers and even books growing out of the conferences. Among them are: State Building as Lawfare: Custom, Sharia, and State Law in Postwar Chechnya (Cambridge University Press, 2023) by Egor Lazarev (GSAS 2018), and Post-Soviet Graffiti: Free Speech in Authoritarian States (University of Toronto Press, 2025) by former Visiting Scholar Alexis Lerner.

Cooley is particularly proud of two accomplishments achieved with the Carnegie grant. One is the Harriman Institute’s work on transnational repression, which started with a Carnegie-funded workshop in 2018, “Political Exiles, Transnational Repression and Global Authoritarianism in Eurasia and Beyond.” That work helped lead to the inclusion of transnational repression as one of the issues analyzed in the U.S. State Department’s 2022 annual Human Rights Report. From 2019–21, Freedom House’s work on transnational repression was led by workshop attendee Nate Schenkkan (MARS-REERS ’11), and then taken over by Harriman’s 2017–20 Carnegie-funded postdoctoral research scholar in Russian Politics, Yana Gorokhovskaia (see here).

The Harriman Institute’s anti-kleptocracy initiative was another innovation, which “convened a lot of meetings in understanding anti-corruption tools even before the war started,” Cooley said. In collaboration with Matthew Murray, an anti-corruption expert at Columbia’s School of International and Public Affairs, Harriman helped bring together academics, practitioners, and activists “in the anti-corruption space,” said Cooley. Ultimately, he said, the Carnegie grant not only “provided a nice infrastructure for a number of Harriman scholars to explore Russian-related topics,” but also “expanded the Harriman’s network in New York and beyond.”◆

Featured photo: Left to right: Alexander Cooley, Michael McFaul, Stephen Cohen and Joshua Tucker during the public debate between Cohen and McFaul in 2018. All photographs in the piece are from the same event